Students in CO4494 Bulldog Online Newsroom ask, 'Can AI do what journalists do?'

By Josh Foreman

Instructor for CO4494 - Bulldog Online Newsroom, Spring 2024

The ‘Talk of the Town’ in 2024

Journalism educators are talking a lot about AI. Specifically about generative AI — the kind of AI that can create new content.

Until OpenAI “introduced” ChatGPT to the public in November 2022, AI seemed like an abstract concept. Felix M. Simon, who published a thorough study of AI in journalism earlier this year, described the change: “What had previously been a relatively slow-burning development … is now the talk of the town.”

We are all talking about it, about how it will change journalism, about how to use it ethically, about whether to use it at all. I have heard a maxim repeated in the last year and a half: “AI is a tool.” Tools are useful — the maxim is hopeful.

Simon, who conducted upwards of 200 interviews with journalists and experts, identified a feeling of “uncertainty, hype, and hope” as a primary motive for the adoption of AI among journalists. We all hope AI is a tool, and we all know that if it is a tool we should learn how to use it.

At the Mississippi Press Association student conference in March, Dr. Debora Wenger, a professor of journalism at the University of Mississippi, relayed a prediction she had heard regarding AI in journalism: AI will not take a journalist’s job, but another journalist who knows how to use AI will.

Drew Ortiz, the Life Sapper

I have felt less hope about how AI will improve journalism, and more fear about how AI might harm journalism. I worry that we will get more content from the likes of Sports Illustrated’s Drew Ortiz, who “has spent much of his life outdoors, and is excited to guide you through his never-ending list of the best products to keep you from falling to the perils of nature” — and who was discovered to be an AI-created persona writing AI-created stories.

I don’t want to read any content produced by the likes of Ortiz. When I even hear the name “Drew Ortiz” my spirit sinks a little. I asked my students to imagine a world in which AI-generated writers create AI-generated stories, which are read by AI-generated readers…

Underlying my skepticism of AI in journalism is the sincere belief that AI will never be able to do what good journalists do, and what makes good journalism popular with readers. Journalists go into the world and interview people, record details with their senses, use their minds to turn issues over and over, creating insights.

To generate content, AI needs existing content to mine; Ask ChatGPT to summarize Dak Prescott’s career, and it will produce a summary with facts and statistics. But ask ChatGPT to tell you about an average person in your community, and it is utterly incapable.

One UK-based editor cited in Simon’s study summed it up: “The job of journalism is to find stuff not on the internet already. Artificial intelligence won’t be able to do that.”

The Great Unknown Project

At the beginning of this semester, I spoke with students in CO4494 Bulldog Online Newsroom about a project that could affirm the unique and necessary role of journalists in a community. For the project, I asked students to write about people in the community who have interesting stories, and who have not had their stories told before. As part of our project, we would challenge the generative AI tools ChatGPT and DALL·E to tell us about, and depict, those people.

My prediction was that AI would fail at the task. We called the project “The Great Unknown” because of the speculation surrounding how AI will transform journalism and society. And because the people we would write about were “unknown,” in the sense that media had not told their stories before.

The result of the project shows that in most cases, ChatGPT failed to tell us anything. The closest ChatGPT came to succeeding was a summary of Asia Aaron’s struggles with social media scrolling; but the AI summary was generalized, and could have fit with any story about a person struggling with scrolling.

DALL·E was able to show us those people, however — or at least perverse approximations of those people. For example, DALL·E’s version of Sarah Morgan Pellum, a young Starkville entrepreneur, had mismatched eyes, disjointed facial features, and gripped a coffee drink with six-fingered hands. The AI-generated images were largely disturbing.

Each of the stories that follows contains fully human-created photos and writing, along with the results of our AI queries. The contrast between them illustrates that, as we predicted, AI simply cannot fill the most crucial roles of journalists.

When Megan Gordon tells the story of Willie “Sunshine” Coleman, a beloved Starkville elder who spends his days spreading positivity in his community, she is creating a win-win-win: Megan wins, by creating and sharing a worthy story; Coleman wins, by having his humanity recognized by his community; Readers win by learning about an interesting community member. The wins go on.

Should we use AI at all?

I didn’t quite realize when we started this project that the question of whether to use AI in journalism has already been answered. When we started the project, I didn’t think about how our student journalists here at Mississippi State have already widely adopted the use of Otter.ai to transcribe interviews. The tool transcribes audio in real time, even summarizing and categorizing interviews. The result is fully transcribed text that a journalist can draw on while writing. And to make things even more efficient, the text is searchable. I didn’t think about how in CO3403 Photographic Communication, we already learn to use Adobe’s AI tools in photo editing: to select subjects, reduce graininess, make panoramas, fix blemishes, and more. I didn’t think about how when I frequently search newspapers.com for research and teaching examples, I’m using its AI-powered text recognition software to navigate the 900 million pages the company has digitized.

So it’s really not a question — AI is a tool, and we are already using it casually and frequently. Some of the stories that follow were made with the help of Otter.ai transcription. But, even such a useful AI tool needs supervision; when Ivy Rose Ball interviewed a man named Raja Reddy, the software transcribed his name as “Maria Rodriguez,” and replaced male pronouns with female pronouns in the interview summary.

I hope that the Great Unknown project will show that journalists are crucial for the continuation of the win-win-win process that contributes to the health of a community. And I hope you enjoy these seven stories — stories that before now have not been told. Our students have undertaken one of the great life-affirming acts: creation. They have made their subjects feel seen. We get to benefit from their hard work.

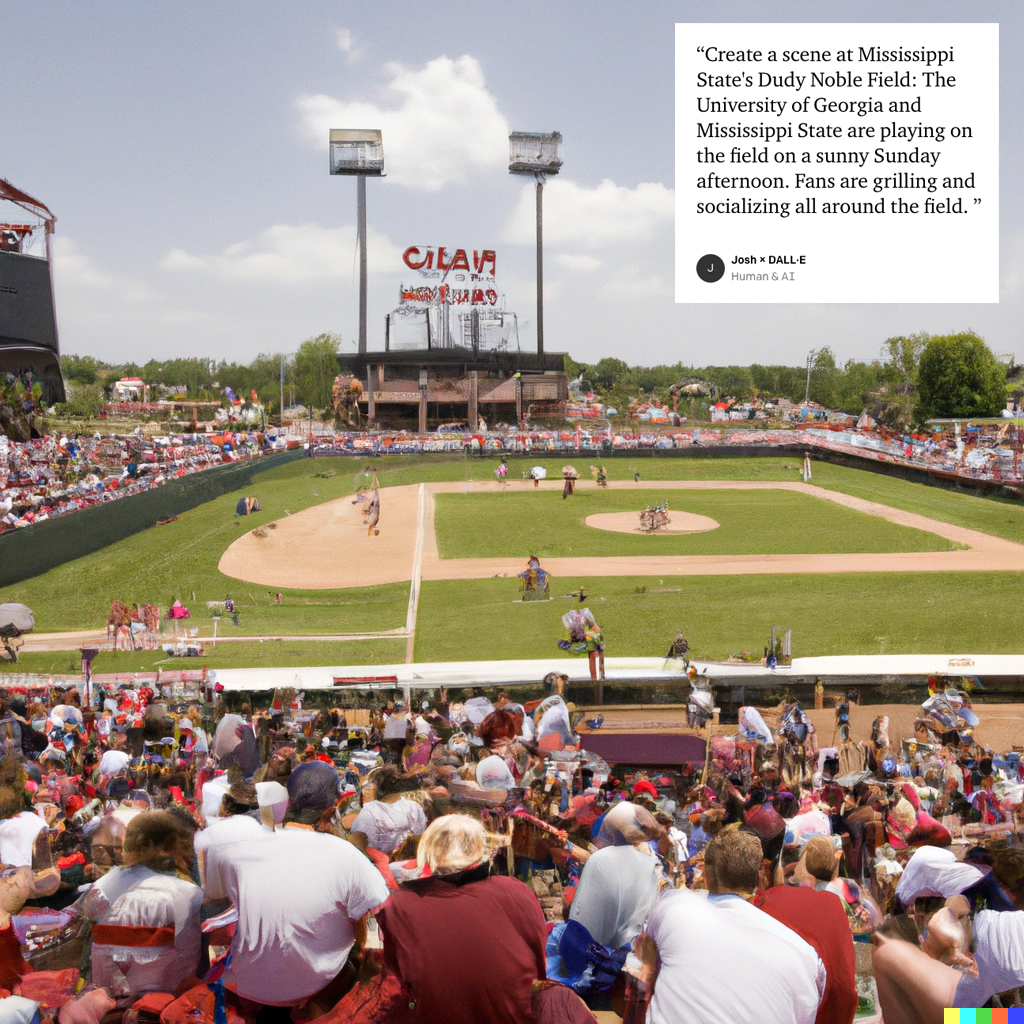

And the benefits extend, beyond the web and beyond the classroom. Walking along Dudy Noble’s left field concourse on a recent Sunday afternoon, past fans grilling steak while University of Georgia players in their bright red jerseys stood below, I recognized a bearded face. It was Micah Graves, a chef for Mississippi State athletics. I had never met him, but I felt like I knew him; one of my students, Lizzie Tomlin, had written a wonderful story about his rise.

“You’re the chef,” I said. “I read your story.”

I shook his hand, and smiled. He smiled at me. Our hands pressed together. It was real.