By Sera Zell Walton

The Ardennes Forest, located in southeast Belgium, stands resolutely, a force of nature. Life in the forest rises from the soil, fed by the decay of past flora and fauna. Trees shelter plants, animals, and sometimes soldiers. Fighters from the Battle of the Frontiers, the Battle of Sedan, and later, U.S. Army troops in the Battle of the Bulge, all moved through its depths.

In 1944, soldiers from the VIII corps found refuge in the Ardennes, making homes out of hastily dug fox holes and finding warmth from the body heat of the soldiers to the left and right of them. They searched the sky for salvation, but a body of towering pines with snow-covered, low hanging branches clouded their view, perhaps mirroring the spirit of these war-battered soldiers. With every step, the frozen ground crunched with ice and unforgiving temperatures biting at the soldiers’ boots and bones. With every spoonful of rations, the freezing food invited the frigid temperature into their stomachs and souls. The howling wind was a screaming battle cry from the forest, snugging out their campfires and blowing out every soldier’s last best friend - a cigarette.

When day turned to night, their new home turned into an abyss, and fear of the enemy filled their minds. Here, in the darkness, the Ardennes became, not just their battleground, but the wild wilderness waiting to swallow them whole and make new life out of them, just as it did with the soldiers before them.

Under their commander, Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton, the VIII Corps left behind memories from the famous Cotentin Peninsula and Battle of the Brest, moving north toward the high-traffic city of Bastogne, toward Belgium and ultimately toward the "Ghost Front."

Thanks to the dense vegetation from the Ardennes, most commanders viewed Bastogne as an untouchable playground and unlikely target. Allied commanders found the area unable to support tank operations, and subsequently deemed this part of the front a rest area for tired troops.

“I want a man who knows how to fight. Get me Troy Middleton”

Troy Middleton, a seasoned veteran and Mississippi State alumnus, had decades of combat experience. He had earned respect from allied leaders. He was ultimately invited to the front by Gen. George Patton. After firing Maj. Gen. Emil F. Reinhardt for his lack of combat experience, Patton said, “Get rid of him. I want a man who knows how to fight. Get me Troy Middleton.”

Patton and Middleton were old friends who had met at the Command General Staff College in Leavenworth, Kansas. Both being significantly younger than most majors at the course, Middleton and Patton connected and formed a friendship that would prove to be lifelong.

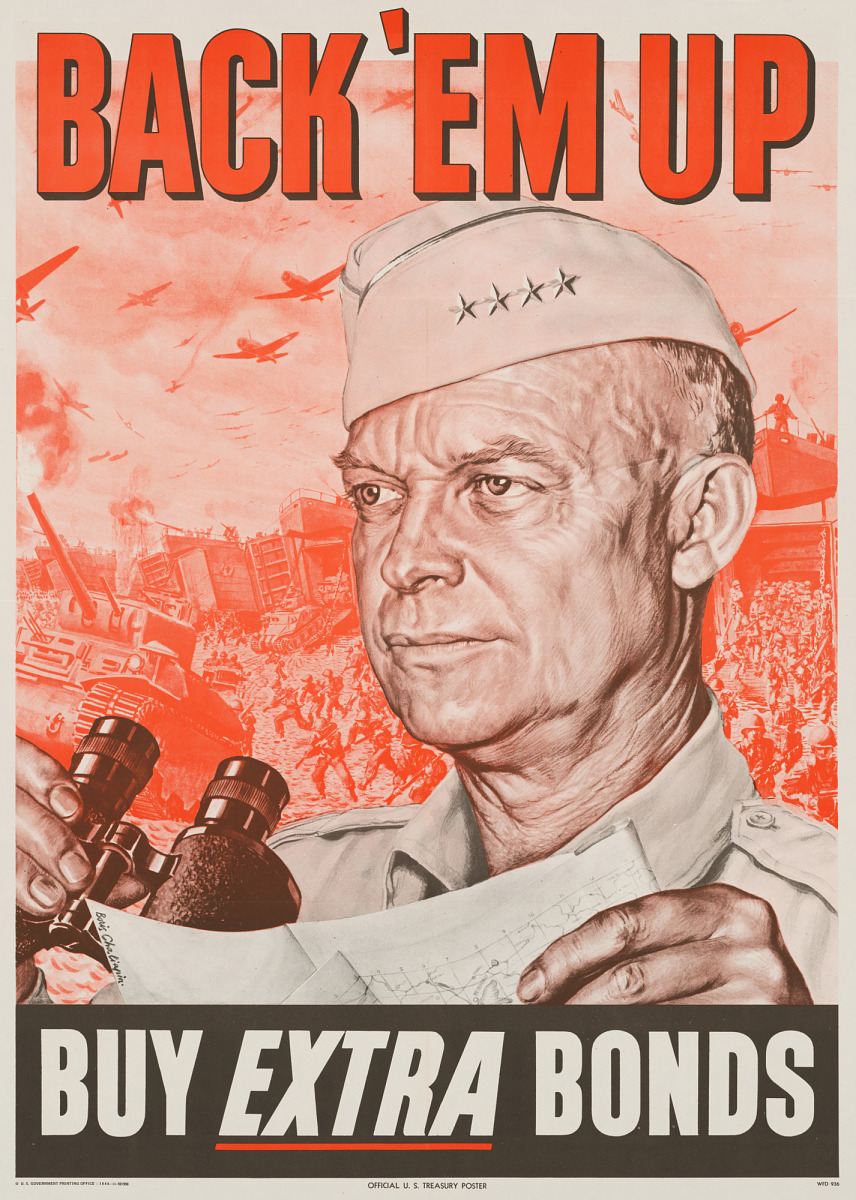

Middleton performed so well at the Command General Staff College that he was invited to teach the course to incoming classes from 1924 to 1928. This is how he met yet another famous friend: Dwight D Eisenhower. Middleton’s influence extended beyond just Eisenhower and Patton, with many of his former students rising to command during World War II.

Eisenhower seconded Patton’s desire to bring Middleton to the fight. In 1959, the Starkville Daily News quoted Eisenhower's thoughts on Middleton: “There was a certain corps commander in the United States that I wanted to get over into Europe immediately. And I got a telegram saying, well, sure, he is a fine man, but he is so crippled out in Walter Reed that the doctors won’t assure you that he can’t move around. And I said, you send me the man and I will send him into battle on a litter, because he can do better that way than most people I know."

When Middleton arrived in Europe, he met Eisenhower in London. Before he left to join the VIII Corps, Eisenhower asked Middleton what he thought about bringing Patton back to command. Middleton recalled, “Ike was wary. I said I thought it would be a good idea to bring Georgie back because he’s such a fighter. Ike agreed with that but remained leery of Georgie’s big mouth.”

And so, Middleton was picked up in London by his driver and headed to Northern England, perhaps reminiscing on the 172-mile train ride from Copiah County to Starkville that he took at just 14 years old. The train ride that began his college education at Mississippi A&M and ultimately his military career.

It was there, in Northern England, months before Middleton or the VIII corps ever reached the Ardennes, that they spent their time preparing for one of the most famous battles in history – D-Day.

He was not only given the role of planning, but also the role of creating war fighters out of young draftees. Middleton was well accustomed to developing young men. During his days at Mississippi A&M, he quickly fell into the military lifestyle and rose to the top of the regimented military life before him. By his junior year, Middleton earned the rank of Cadet Command Sgt. Major, giving him the responsibility of ensuring the discipline of hundreds of other cadets. After excelling in this role, Middleton was given the position of Cadet Lt. Colonel his senior year, where he commanded more than 700 cadets. As Cadet Lt. Colonel, Middleton couldn’t have possibly known in his first command that his last would be leading over 25,000 soldiers in the largest and bloodiest battle fought by the United States in WWII.

VIII Corps Marches through Europe

Though the VIII corps did not take part in the initial landings on Normandy, they did take up defensive positions west of Carentan and the Cotentin Peninsula. After over a month of fighting through the French backcountry, the corps took part in Operation Cobra, the allied breakout from Normandy starting on July 26, 1944. They played a key role by liberating Avranches, France on July 28, 1944. By July 31, 1944 Operation Cobra was complete and the allies were one step closer to liberating Paris.

After breaking out of Normandy, the VIII corps was ordered to head west to assist in the liberation of Brittany, with the goal of taking important harbors that could later be used to resupply troops in France. Knowing this was key terrain, the Germans did everything in their power to fortify these ports, especially at Brest.

By Aug. 7, 1944 the Americans had reached Brest, but much to their dismay they found the city impenetrable. According to an article titled Forgotten Fights: Assault on Brest, August-September 1944 by Ed Lengel, “The next two weeks passed slowly as American forces slowly encircled the city and the Germans further improved their defenses. Finally, General Omar Bradley dispatched General Troy Middleton’s VIII Corps, with the 2nd, 8th, and 29th infantry divisions and Ranger detachments to storm the city. After some preliminary attacks, the full assault, backed by artillery and strikes by aircraft using bombs, rockets, and napalm, began on August 26.”

After Gen. Eisenhower authorized American troops to “utilize maximum number of aircraft which can be effectively employed in support of this operation,” Middleton carefully reconsolidated his troops for his Sep. 8 offensive which resulted in 11 more days of fighting and the eventual surrender of the Germans. After nearly 10,000 deaths, the Americans found Brest harbor facilities to be too destroyed for use.

After reorganizing after the extensive fighting in Brittany, Middleton’s troops moved to the boarder of Germany and took over the front in the Ardennes and Our River by Oct. 8, 1944. Though, Middleton’s command had already been tested in places like Brest and the Cotentin Peninsula, but nothing could prepare him for what awaited him in the frigid forests of Belgium.

The Battle of the Bulge Begins

In “Troy Middleton: A Biography” by John Prince, Middleton recalled being startled awake by the booming German guns. On the misty Saturday morning of Dec. 16, 1944, the Germans launched a carefully curated offensive relying on tempo and surprise, which was easily achieved given the difficult terrain. It was a plan so audacious that Omar Bradley’s chief of staff later said that predicting what Hitler would do next would require forecasting the “intentions of a maniac,” James Early said in The “Hitlers Last Gamit: The Battle of the Bulge” episode by Key Battles of American History.

That morning Wehrmacht moved tanks and infantry straight to the Americans, along with almost 2,000 artillery pieces. “I could hear the big guns there in Bastogne. By 10 a.m. I had word that element of sixteen different German divisions had been identified in the attacking force,” Middleton said.

After the initial shock of the attack, Middleton went straight into understanding his positions. His first thought was to get a status update on the 106th Division, known as the Golden Lions, located at Schnee Eifel. Middleton was rightfully concerned and discovered that the 106th’s 422nd and 423rd Regiments had not retreated and were located on the German side of the Our River.

Middleton made a point to regularly meet and share meals early in their occupation of the Western Front with these men due to their extremely exposed position compared to the rest of the VIII Corps. He even recalled sitting with an artilleryman from Ponchatoula and remembering “the good strawberries from back home.” What the Golden Lions didn’t know as they shared lunch with their commander was that their free days were numbered, and they would spend the rest of the war in a German prison camp.

By the next day, the two units were surrounded completely by Germans and the men were forced to fight to the death or surrender to one of the most ruthless enemies America has ever faced. The Ghost Front materialized.

The 106th was just the first to fall. The 109th and 110th would fall too, but not without a fight.

Due to fuel shortages, the German offensive relied on reaching Bastogne and capturing American fuel depots by the first or second day. Thanks to members of the 110th, the Germans had been delayed 37 hours, which initiated the logistical downfall that cost the Germans the battle and the war.

After hearing from 110th Infantry Regiment Commander Col. Hurley Fuller, writing from a German prison camp, Middleton send him the following letter on April 19, 1945:

“I have received your letter with much pleasure, it being the first information I have received on the fact that you are very much among the living. I made many inquiries concerning you, and also had a search made for the Clervaux area, but received nothing which would lead to your whereabouts. If General Cota prepared the citation for the 110th Infantry, I will certainly send it forward with a strong endorsement. I went over the ground where your unit fought it out with the Krauts, and left with sufficient data to leave no doubt in my mind that your outfit did a magnificent job. Had not your boys done what they did, the 101st Airborne could not have reached Bastogne in time. As you know, with an 88-mile front, we were stretched very thin. However, the whole outfit gave a good account of itself and the Kraut took an awful beating. On the offensive which followed, we advanced straight through the northern half of our old front and on to Adenau, where we were in 1918-1919. There through which we advanced was a graveyard of destroyed German tanks, guns and vehicles.”

After these debilitating blows and the Germans swarming in on Bastogne, Middleton knew exactly who he must bring in – the 101st Airborne division, his old friends from Normandy.

While waiting for the famous Screaming Eagles, Middleton was ordered to leave Bastogne and move to Neufchâteau on Dec. 18. Knowing that this would mean losing Bastogne, Middleton stayed overnight and waited to share the importance of holding the famous city to the interim commander of the 101st, Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe.

In his book “Soldier”, Maj. Gen. Matthew Ridgeway recalled the circumstance of the VIII corps when the 101st Airborne arrived. “Just about dark we found the command post of General Troy Middleton’s VIII Corps. The gloom inside that headquarters was thicker than the fog outside. This atmosphere of uncertainty was in no way the fault of Middleton, a magnificent soldier with a wonderful combat record in two wars. But the most disquieting thing in any war is being in a completely unknown situation. General Middleton knew that some of his units had been overrun. He knew the German attack had opened a great gap in his lines. But nearly all his communication with his forward elements were out, and he had no knowledge of where his forces were, nor where the Germans were, nor where they might strike next,” he said.

So, in the wake of uncertainty with the hearts of fighters, the screaming eagles flew in crying the sound of freedom as they took the role of the “Battered Bastards of Bastogne.”

For years to come, many commanders would recall Middleton’s determination to hold Bastogne and commend him for his decision that ultimately made the Battle of the Bulge the last largescale German offensive in World War II. Most famously, Patton called it a “stroke of genius.”

Life After the War

Unsurprisingly, after the Battle of the Bulge, the Germans no longer had the morale, mass, or logistical support to continue their offensives, and the German army was defeated five months later on May 7, 1945.

After the war, Middleton returned to his peaceful lifestyle in Baton Rouge and requested his pre-wartime job of comptroller at Louisiana State University. In April of 1946, Middleton was appointed to the Doolittle Board to investigate officer-enlisted relationships, given his experience as both an enlisted man and officer.

From 1951 to 1955, Middleton was called to serve at the United States Military Academy at Westpoint on the board of Supervisors. A rather ironic job, considering the Reveille, Mississippi State University's yearbook, stated that he intended to attend the Academy after graduation. A goal which obviously fell through.

His Reveille biography reads, “The Colonel comes from Hazelhurst and has been here long enough (five years) to have become renowned. He has taken great interest in military and was rewarded this year by becoming commissioned with the highest rank of the student body. He had taken some interest in Athletics and made a good man on the Class Football Team. From his record above you may have observed his popularity. He is another worshipper at the shrine of Venus, and you may often find him dreaming of his lady love. “Teddy” has many friends. He expects to enter West Point.”

Simultaneously, in 1951, Middleton took on the role of President of Louisiana State University to spend more time with his wife, Jerusha Collins Middleton. The General retired in 1962 but continued serving as president emeritus.

The 1972 edition of the Alumnus, a Mississippi State magazine, said “the General still keeps regular weekly office hours as president emeritus. He and Mrs. Middleton live a short distance from the university on a three-acres wooded site where they built their dream home, a two-story, Spanish-style house that resembled one they saw in the Philippines.”

General Troy Middleton passed away on Oct. 6, 1976, three days before his 83rd birthday.

Middleton’s legacy continues at Mississippi State University through the Army ROTC program where dozens of cadets commission each year with dreams of following in his footsteps.

Where do they prepare for this seemingly impossible task? Middleton Hall – a two story, red brick building with creaking hardwood floors, a noticeable lack of sufficient air conditioning and an oil painting of Troy Middleton as Cadet Sgt. Maj. to the left of the stairway. Once commander at the Ghost Front, now a ghost commander ensuring his noble legacy in the 113-year-old building.

A World War II M8 Carriage Howitzer, now painted maroon and shot at school football games, sits out front of the hall and serves as a reminder of not just the sacrifice of Troy Middleton and his family, but of all his soldiers.

In 1953 Middleton answered the question, ‘What does State College represent to you?”

He answered, “The place which gave me the incentive to become whatever success I have achieved.”